The Marked Woman: Unpacking the Myth of the Tattooed Prostitute and the Allure of the 'Deviant' Canvas

- thebluebloodstudios

- Jun 25, 2025

- 6 min read

We've all heard the old adage, whispered or outright stated, that "tattoos used to be for sailors and prostitutes." For sailors, as we've explored previously, tattoos were badges of honor, travelogues etched in skin, and powerful talismans against the whims of the deep. But what about the other half of that famous pairing? The notion of the tattooed prostitute: was she a widespread historical reality, a cultural invention, or something in between? And how does this historical shadow still linger on heavily tattooed women today, transforming the very act of body art into a statement of daring self-expression?

At The Blue Blood Studios, we believe in celebrating all forms of self-expression and challenging the lingering prejudices that obscure the artistry and personal significance of tattoos. Let's cast off into the intriguing, sometimes murky, waters of history to navigate this perception.

The Sailor's Canvas and the 'Fallen' Woman: A Collision of Worlds

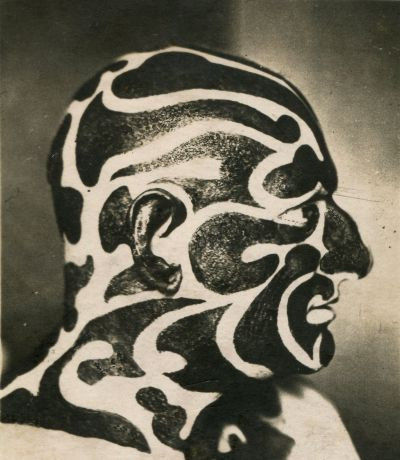

As the 19th century unfurled, tattoos, freshly rediscovered by Western sailors from the Polynesian islands, exploded in popularity among seafaring men. They were tough, often unlettered, and their bodies became living maps of their adventures and beliefs. But ashore, particularly in Victorian society, where rigid morality reigned supreme, tattoos quickly became associated with the "fringe." This included sailors, yes, but also circus performers, soldiers, and, inevitably, those deemed "social outcasts," a category into which prostitutes were firmly, and often cruelly, placed.

Here's where the "idea" of the tattooed prostitute really took hold. It wasn't necessarily that women in sex work universally chose to get tattoos as a professional mark, in the way a sailor might get an anchor for a transatlantic crossing. Instead, the connection was often forged in the crucible of social judgment and stigma.

The Mark of the 'Other'

In a society obsessed with respectability, a woman with a visible tattoo was instantly flagged as "deviant." Her body, if adorned with tattoos, was seen as uncontrolled, less "pure," and thus, implicitly, she was "available" or "fallen." Prostitutes, already outside the bounds of conventional society, were an easy target for this projection. A tattoo became a convenient visual shorthand for a woman who defied norms.

Figures like the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso, in his flawed "scientific" studies, went so far as to claim that tattoos were a sign of "atavism," a throwback to a more primitive, criminal nature. In his mind, prostitutes were inherently "criminal" or "degenerate," and therefore, any tattoo on their skin simply served as further "proof" of their supposed character. This harmful, pseudo-scientific thinking cemented the public's negative perception.

Popular press and sensationalized accounts of urban life often depicted "painted women" with tattoos, weaving narratives that blended vice, rebellion, and exoticism. These stories, while perhaps not always rooted in widespread reality, etched the image of the tattooed prostitute deeply into the public imagination.

Ultimately, while not necessarily a widespread professional practice for sex workers in the same way sailors adopted tattoos, the tattoo on a woman automatically placed her in a category that, to the moralistic eye, often overlapped with prostitution. It was more about the perception of deviance.

The Enduring Gaze: How History Shapes Modern Perceptions

While society has come a long way, the echo of these historical perceptions persists. Today, a man with a full sleeve or a back piece might be seen as edgy, artistic, or simply expressing himself. A woman with similar coverage, however, can still face a different set of reactions. The Victorian era's judgmental gaze, which so readily conflated tattooed women with "fallen" status, might seem archaic. But it laid the groundwork for a subtle yet persistent undercurrent: that a woman who adorns her skin with tattoos is, in some way, different, and that difference can still be misinterpreted.

A heavily tattooed woman today still navigates a landscape where her markings can elicit judgment. She might be seen as:

Rebellious: Still challenging conventional beauty standards that prize "unblemished" skin.

Strong and Independent: Her choices speak volumes about her autonomy over her own body.

Creative and Expressive: Her skin is her personal art gallery, a testament to her unique story.

"Alternative": Even in 2025, a significant amount of ink can still place a woman outside the traditionally "corporate" or "conservative" aesthetic.

This double standard highlights that while tattoos are more mainstream, gender still plays a significant role in how they are perceived on the body. Despite growing acceptance, heavily tattooed women often report more significant challenges in certain professions, facing assumptions about their professionalism or competence. They might still encounter unsolicited comments, stares, or assumptions about their lifestyle, intelligence, or even their sexual availability. There's also a pervasive notion that women get heavily tattooed solely to draw attention, rather than for personal meaning or artistic appreciation, which undermines their agency and intent. Some may even question a heavily tattooed woman's femininity, clinging to outdated ideas of what a "proper" woman should look like, devoid of "defacing" marks.

Unpacking the Conflation: Tattoos on Women and Mental Health

A concerning stereotype that occasionally resurfaces is the conflation of tattoos on women with mental health issues. This notion is often rooted in outdated psychological theories or misinterpreted data.

The Claim and its Origin

Historically, early psychological studies (often from the mid to late 20th century) sometimes attempted to link tattooing with "deviant" behaviors or personality disorders. These studies were often based on small, unrepresentative samples, frequently drawn from clinical populations, prisons, or military recruits. They operated under the assumption that getting tattooed was inherently a sign of rebellion, impulsivity, or underlying psychological issues, rather than a form of cultural or personal expression.

When these flawed studies focused on women, the bias was amplified by existing societal prejudices. If a woman had tattoos, it was easier for some to attribute it to a "disorder" or "instability" rather than agency or artistic choice, reinforcing the idea of female "delinquency."

Reliability and Research Analysis

How Reliable Is This Information?

Not very reliable at all, especially by modern scientific standards. The methodologies of many of these older studies would be considered deeply flawed today. They often suffered from:

Confirmation Bias: Researchers sought to confirm pre-existing biases about tattooed individuals.

Sampling Bias: They didn't study the general population, but rather specific groups already labeled as "problematic." It is not possible to generalize findings from a prison population to the entire population of tattooed women.

Lack of Control Groups: Often, there was no comparison to non-tattooed individuals with similar backgrounds.

Outdated Psychological Frameworks: The very understanding of mental health and personality has evolved significantly since these early studies.

Modern Research and What It Shows:

Contemporary, well-designed research paints a very different picture. While some studies might find slight correlations between certain personality traits (like openness to experience or a degree of risk-taking) and getting tattoos, there is no robust, consistent, and reliable scientific evidence to suggest a causal link between getting tattooed (especially for women) and having mental health issues or disorders.

In fact, modern psychological perspectives often highlight the positive psychological benefits of tattoos:

Identity Formation: Tattoos can be crucial for developing and expressing personal identity.

Coping Mechanisms: They can serve as powerful tools for healing from trauma or managing mental health struggles, providing a sense of control and transformation.

Boost in Self-Esteem: A well-chosen and executed tattoo can significantly enhance body image and confidence.

The idea that heavily tattooed women inherently suffer from mental health issues is a harmful stigma, not a scientific finding. It's a way to pathologize and dismiss a form of self-expression that doesn't conform to traditional expectations of femininity.

The Allure of the Adorned Body: From Stigma to Statement

Yet, within this shadow of stigma lies a fascinating truth: the very act of adorning oneself, against societal norms, carries an inherent power. For women, especially, choosing to permanently alter one's body in a way deemed "unladylike" was, and still is, an act of quiet, or not so quiet, rebellion.

Think of the "tattooed ladies" of the circus sideshows; often heavily adorned, they made a profession out of their "deviance," transforming societal judgment into a spectacle of awe and fascination. They might have been deemed "outside," but they commanded attention, defying the invisibility often imposed on women of their era.

Challenging the Narrative: Tattoos as Empowerment and Expression

Despite these challenges, tattoos for women today are overwhelmingly a source of strength, empowerment, and profound personal meaning.

Reclaiming the Body: For many, tattoos are a way to reclaim autonomy over their bodies, especially for survivors of trauma, allowing them to transform painful memories into symbols of resilience and healing.

Artistic Self-Expression: Heavily tattooed women are living canvases, boldly showcasing incredible artistry and their unique aesthetic vision. Their bodies become a testament to their love for art and self-curation.

Confidence and Authenticity: Embracing extensive tattoo work often signifies a deep level of self-acceptance and a refusal to conform to societal pressures. It's a powerful statement of "this is me."

Community and Connection: Tattoos can be a gateway to vibrant communities, connecting individuals through shared interests, artists, and the culture of body art itself.

Narrative and Identity: A tattoo can tell a story: of triumph, loss, love, growth, or belief. Heavily tattooed women carry their life's journey visibly, turning their skin into a personal memoir.

Conclusion: Celebrating the Art and the Individual

At The Blue Blood Studios, we recognize that every tattoo, regardless of who wears it, is a personal statement. For heavily tattooed women, this statement often carries an added layer of courage and resilience, challenging centuries of misconception and prejudice. Their tattoos are not marks of deviance or distress, but powerful declarations of art, identity, and personal freedom.

It's time to look beyond outdated stereotypes and appreciate the wealth of stories, strength, and beauty that heavily tattooed women bring to the world. Their skin is their canvas, and their choices are their own.

Comments